The Setting: Panji & Majapahit

The origin of Panji stories was thought to be from the 13th century East Java or earlier, as suggested by the inclusion of the kingdom "Singhasari" in some versions of the stories that exist today[1][2]. Singhasari was the precursor kingdom of Majapahit, and the histories of the two kingdoms were always interlinked that it would be difficult not to mention the former kingdom while discussing the latter one[3]. While it is likely that Panji stories had existed since before Majapahit era, the stories grew to become popular during Majapahit era. This is evident from the depictions of Panji that were carved in numerous Majapahit-era temples[4]. Some Panji scholars also believed that the spread of the stories to other regions in Southeast Asia was linked to the expansion of Majapahit kingdom during its heyday[5][6], though some others believed that it happened much later[4][2].

While Panji is a quintessentially Javanese Majapahit story, there has never been a true, original Majapahit Panji manuscript that exists today that we can refer to[7]. In fact, most well-known Panji stories that exist today were invented and popularised much closer to current time[2]. This might be because the original stories of Panji were spread around mostly through performances, oral communications, and paintings or other arts instead of written manuscripts[5][6]. Yet, all retellings, even the ones from other countries, still maintain the same (or similar) settings and themes, which is indicative of the high regards of the people who adapted the stories to the geographical origin and cultural root of the stories[8][4].

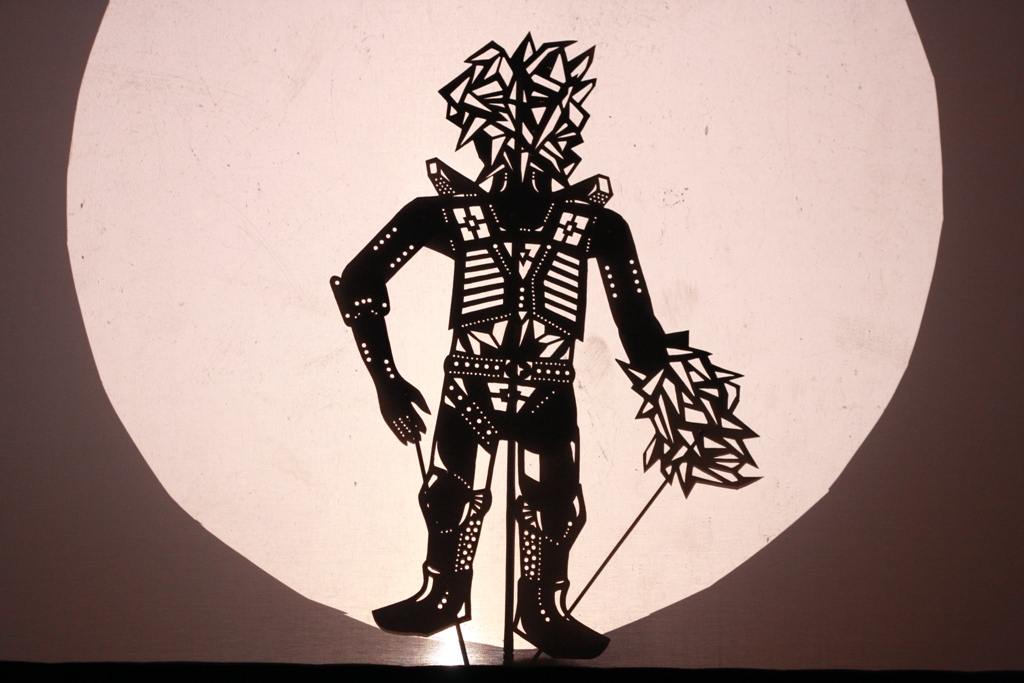

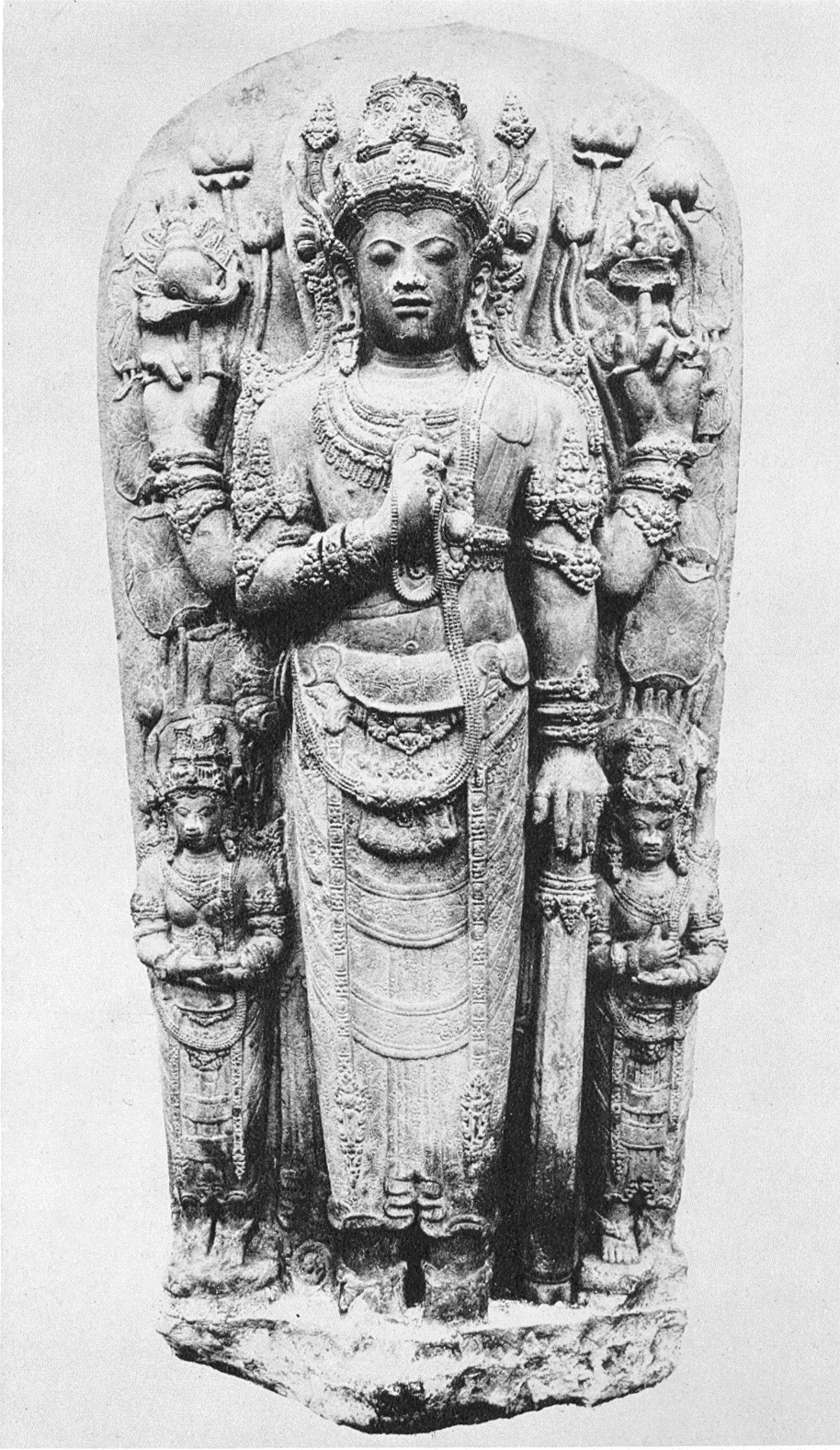

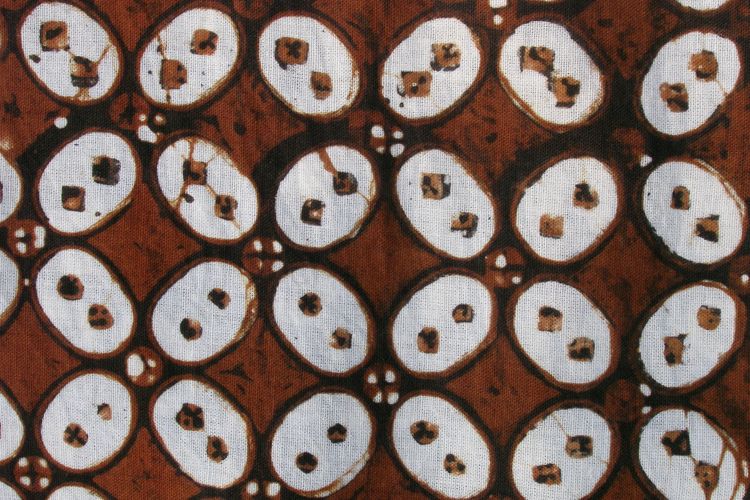

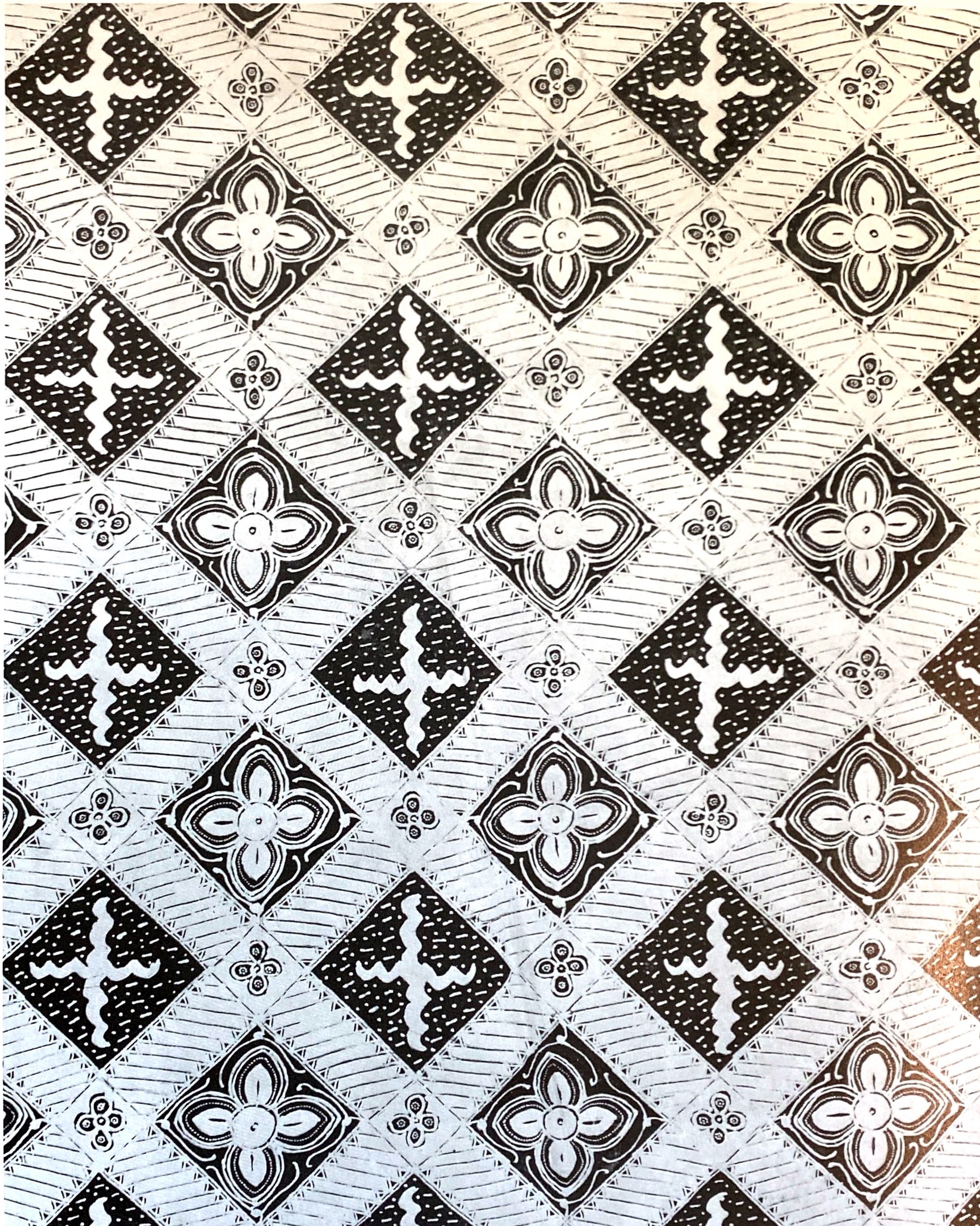

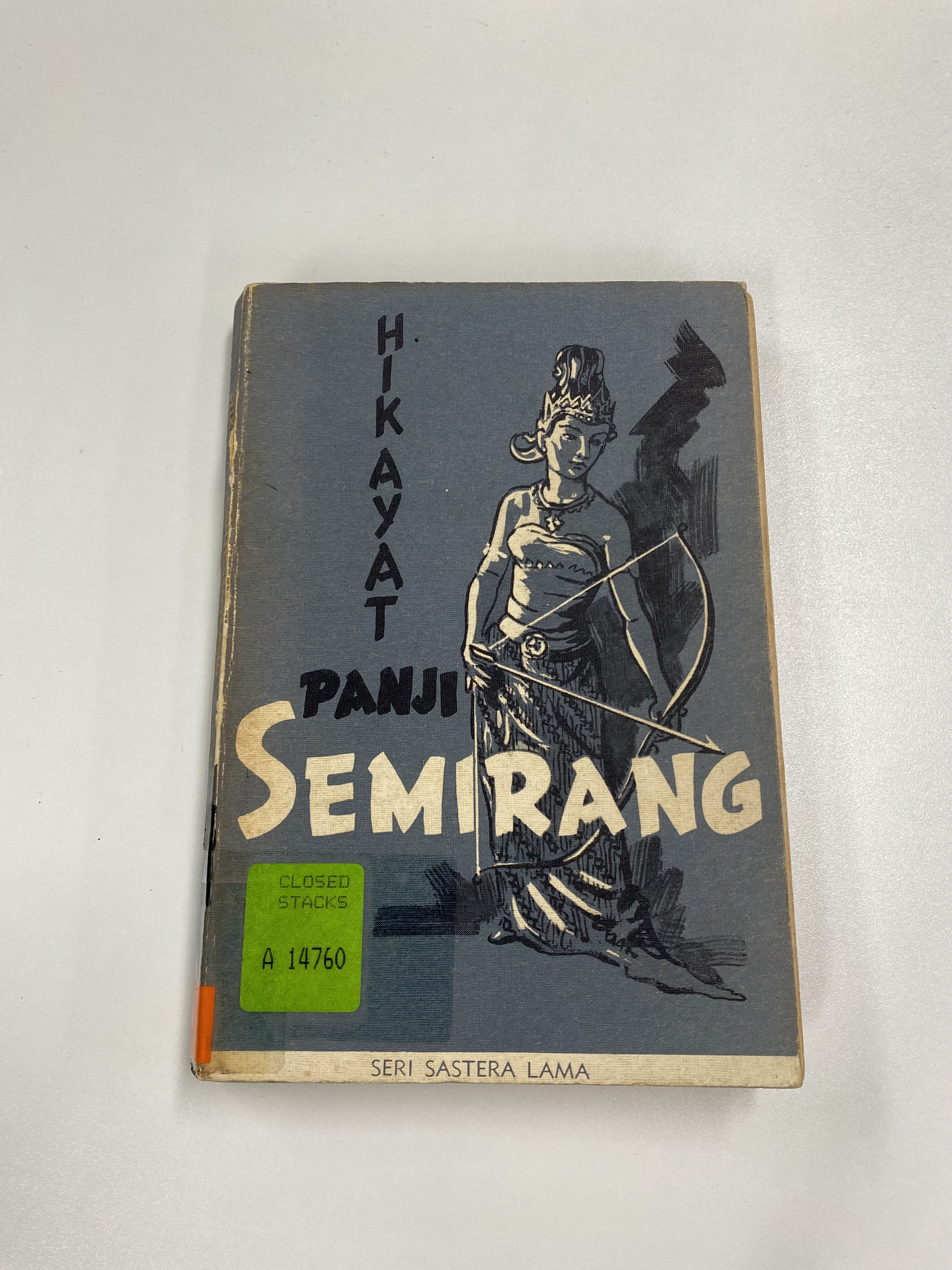

In adapting "Hikayat Panji Semirang" for 360imx, this project will also mostly draw inspirations from Majapahit culture. For example, the layout of palaces and temple complexes, the attire of the characters, and the depictions of food, trades, and other objects are all inspired from archaeological findings, artefacts, and other accounts from Majapahit era. However, as the title of the project implies ("Panji Across SEA"), the emphasis of the project is on the relationships between Southeast Asian countries during pre-colonial times, with Panji as the story that unifies this idea. As such, this project will also feature some objects and traditions from other countries in Southeast Asia in order to enrich the story and match it to the underlying theme. The inspiration to take this approach comes from the book that this project is adapted from. While the story of "Panji Semirang" is still set in Java, the book was written in Bahasa Melayu and printed in Singapore, making it a perfect example of an adaptation that spans "across the sea".

The book originally mentioned four places as the set of the Panji Semirang story, which are: Kuripan (Kahuripan), Daha (Kediri), Gagelang, and Mount Wilis. Kahuripan and Daha were considered the two most important provinces of Majapahit, according to the accounts in Nagara-kertagama[9][1]. The compound of Kahuripan is estimated to be at present-day Surabaya, while Daha stood at where Kediri is now[9]. There was no mention of Gagelang (or Gegelang, or sometimes Gelang-Gelang), in Nagara-kertagama, but it is believed that the territory/province was established only towards the end of Majapahit and has now become known as the city Madiun[10][11]. Mount Wilis retains its name until today. As the project is split into three parts (Act 1: Raden Inu, Act 2: Candra Kirana, and Act 3: Gagelang), it will zoom into Kahuripan, Daha, and Gagelang as the background setting for each act.

Interested in the book "Hikayat Panji Semirang"? Find it at NUS Libraries here. Other versions of Panji tales are also available to read at Singapore-Malaysia Collection!

[1] Munoz, P. M. (2016). Early kingdom: Indonesian archipelago & the Malay Peninsula. Editions Didier Millet.

[2] Liaw, Y. F. (2013). A History of Classical Malay Literature. ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/history-of-classical-malay-literature/62A4BB01FE98AD03D44E256BDDA9633A

[3] Slametmuljana. (1976). A Story of Majapahit. Singapore University Press.

[4] Kieven, L. C. (2017). Getting Closer to the Primordial Panji? Panji Stories Carved in Stone at Ancient Javanese Majapahit Temples – and Their Impact as Cultural Heritage Today. SPAFA Journal, 1. https://doi.org/10.26721/spafajournal.v1i0.172

[5] Vickers, A. (2020). Reconstructing the history of Panji performances in Southeast Asia. Wacana, 21(2), 268–284. https://doi.org/10.17510/wacana.v21i2.897

[6] Manuaba, I. B. (2013). Keberadaan dan Bentuk Transformasi Cerita Panji. LITERA, 12(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.21831/ltr.v12i01.1325

[7] Panji Cerita Asli Indonesia. (2019, January 28). Museum Nasional Indonesia. https://www.museumnasional.or.id/panji-cerita-asli-indonesia-1836

[8] Kieven, L. (2013). Narrative reliefs and Panji stories. In Following the Cap-Figure in Majapahit Temple Reliefs (pp. 19–50). Brill. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctt1w76vm3.7

[9] Pigeaud, T. G. (1962). Java in the 14th Century: Vol. IV (Third edition). Springer. https://link-springer-com.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/book/10.1007/978-94-011-8776-3.

[10] Hanif, M., Samsiyah, N., & Sri Maruti, E. (2020). Panduan bercerita berpasangan juru pelihara situs sejarah Madiun. Scopindo Media Pustaka.

[11] Sisa Peninggalan Kerajaan Gelang Gelang di Madiun Juga Diincar Kolektor. (2014). detiknews. Retrieved 18 May 2022, from https://news.detik.com/berita/d-2478667/sisa-peninggalan-kerajaan-gelang-gelang-di-madiun-juga-diincar-kolektor